As any climate change instructor knows, China’s ability to arrest its burgeoning emissions of greenhouse gas emissions is critical if the globe is to avoid passing critical climatic thresholds. China’s greenhouse gas emissions have risen an astounding 280% since 1990. The nation’s share of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions has now reached 28%, double that of the next highest country, the United States. Its projected 10.4 billion tons of carbon emissions this year will likely be greater than the U.S. and the European Union combined. Moreover, China’s per capita greenhouse gas emissions have recently overtaken those of the European Union.

Some commentators have taken comfort in China’s pledge under the Copenhagen Accord to reduce its carbon intensity (the quantity of GHG emissions in relation to the economic output of a country) by 40-45% from 2005 levels by 2020, as well as the 17% emissions intensity reduction target set in its 12th Five Year Plan (2010-2015). However, a new study published in the journal Nature Climate Change suggests that China may struggle to meet these goals, palpably demonstrated by the 3% rise in carbon intensity between 2002-2009. As the study’s authors conclude, Chinese policy may be “leading away from its ambitious carbon intensity improvement goals.”

Some commentators have taken comfort in China’s pledge under the Copenhagen Accord to reduce its carbon intensity (the quantity of GHG emissions in relation to the economic output of a country) by 40-45% from 2005 levels by 2020, as well as the 17% emissions intensity reduction target set in its 12th Five Year Plan (2010-2015). However, a new study published in the journal Nature Climate Change suggests that China may struggle to meet these goals, palpably demonstrated by the 3% rise in carbon intensity between 2002-2009. As the study’s authors conclude, Chinese policy may be “leading away from its ambitious carbon intensity improvement goals.”

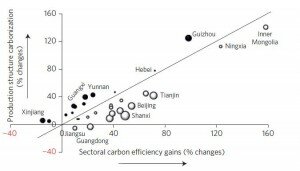

The study, which focuses on the period of 2002-2009, utilized a decomposition technique to assess the significance of two factors that can drive carbon intensity changes: efficiency improvements within sectors and production structure changes.

- China’s commitment to a “carbonizing production structure more than outweighs effects from improvements of sectoral carbon efficiency” in many interior economies that follow the national Great Western Development Plan. For example, Inner Mongolia has focused on highly energy-intensive industrial development, e.g. mining, metal smelting and cement production, with the latter two sectors seeing 14-fold increases in production between 2002-2009. In Guizhou in Southwest China, coking sector production increased by a factor of 11 while carbon efficiency only improved by 60%;

- Large sectors appear to be the primary “laggards” in terms of reducing carbon intensities. It appears that such sectors were given a relative pass in reducing emissions in Western and Central provinces;

- A primary driver of Chinese economic policy in recent years has been capital accumulation, which has proven to be the nation’s most effective mechanism for riding out the global recession. Unfortunately, such policies fuel market demand for large-scale production in energy-intensive sectors, e.g. cement, steel and other emission-intensive processed materials. While the Chinese central government sets both climate and economic targets, the primary factor in evaluating the performance of local governments has remained GDP;

- China has imported and developed many low-carbon technologies, including super-critical and ultra-super critical power plants; the national government could accelerate the penetration of such technologies into areas characterized by high energy intensity, including by linking less-developed interior regions with its developing emissions trading scheme;

- China should explore options of linking its emissions trading scheme with that of the European Union.

Ultimately, the study’s authors conclude that it’s highly unlikely that emissions intensity targets can be an effective emissions control strategy in emerging economies characterized by high economic growth.

This could be a good reading to assign for a module on medium and long-term climate policy making. Among the questions it could generate are the following:

- Should emissions intensity targets considered to be an inadequate commitment per se by developing countries in the post-2020 regime given the results in this study?;

- What incentives could the international community provide to nations e.g. China to increase penetration of low-carbon technologies in inner regions?

- What role can China’s new emissions trading scheme play in bending its emissions trading curve?